Do SAP Consultants Think Differently Because of Business Process Exposure?

15 min

15 min

Do SAP Consultants Think Differently Because of Business Process Exposure?

Three years into his career as an SAP consultant, Michael made an observation that troubled him. He was having dinner with his former computer science classmates, now software engineers at various tech companies, and realized he could barely follow their conversation. They discussed microservices architecture, container orchestration, and distributed systems challenges with enthusiasm and depth. Michael understood the concepts intellectually, but couldn't muster genuine interest.

What troubled him wasn't that he'd fallen behind technically. It was that his mind had reorganized itself around entirely different questions: How do you design a process that works across twelve legal entities with different regulatory requirements? Why do companies structure their cost centers the way they do, and what does that reveal about how they actually make decisions? What makes people follow a documented process versus creating workarounds, and how do you design for actual behavior rather than ideal behavior?

His engineering friends could design elegant technical solutions. Michael found himself seeing the world through a different lens entirely—one structured by business processes, organizational dynamics, and the complex interplay between system design and human behavior. He'd developed what cognitive scientists might call a different "schema"—a fundamental reorganization of how his mind categorized and understood the world.

This isn't unique to Michael. After interviewing over a hundred SAP consultants with various backgrounds—computer science, business, engineering, even liberal arts—a clear pattern emerges: extended exposure to business processes fundamentally changes how people think. Not just what they know, but how they perceive, categorize, and reason about problems.

The question is whether this cognitive transformation makes SAP consultants genuinely think differently, or whether it's simply that they know different things. The evidence suggests the former—that business process immersion creates distinct cognitive patterns that persist even outside enterprise contexts.

The Process Lens: A New Cognitive Framework

Cognitive psychologist Susan Carey's research on conceptual change reveals that expertise doesn't just add information to existing mental frameworks—it sometimes restructures the frameworks themselves. Children don't learn physics by adding facts to their intuitive understanding of motion; they reorganize their fundamental concepts about what motion is.

Similarly, SAP consultants don't just learn business processes—they develop an entirely new cognitive lens through which they perceive organizational activity. This "process lens" manifests in several distinct ways:

1. Seeing Activity as Flow, Not Discrete Events

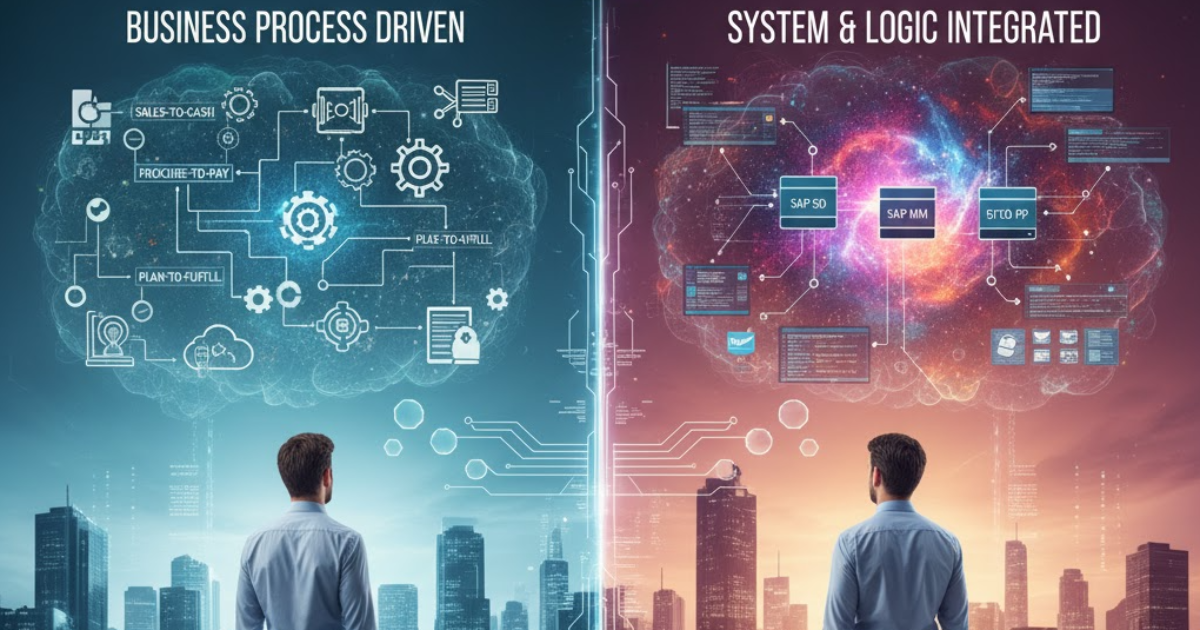

Ask a software engineer/coder what happens when a customer places an order, and you'll typically get an answer focused on the transaction: "The order data is validated, stored in the database, and an acknowledgment is sent to the customer."

Ask experienced SAP consultants the same question, and you'll get something entirely different: "The order creates a commitment in the system that triggers credit checking, inventory reservation, and delivery planning. It generates financial obligations that affect revenue recognition timing. It creates production requirements that ripple through material requirements planning. It establishes a customer expectation that becomes a service-level commitment the operations team must fulfill."

The consultant literally sees different things when they look at an order. Where the engineer sees a discrete transaction, the consultant sees a flow that cascades through interconnected processes, each with their own timing, constraints, and implications.

Research by cognitive linguist George Lakoff on conceptual metaphors reveals that experts in different domains organize experience through different fundamental metaphors. Software engineers think in terms of objects, states, and transformations. SAP consultants think in terms of flows, triggers, and propagations. These aren't interchangeable ways of describing the same thing; they're fundamentally different ways of organizing thought.

2. Constraint-First Rather Than Solution-First Thinking

Present a business problem to a software engineer, and they typically begin with solution generation: "We could build a dashboard, or we could send automated alerts, or we could use machine learning to predict..."

Present the same problem to an experienced SAP consultant, and they begin with constraint mapping: "What's the regulatory requirement here? What audit trail do we need? Who needs to approve this? What's the segregation of duties requirement? What's the integration point with the financial system? What happens during month-end close?"

This isn't pessimism or lack of creativity—it's a cognitive reorientation around constraints. Psychologist Barry Schwartz's research on the paradox of choice reveals that experts in complex domains develop constraint-based thinking because it's cognitively more efficient. When the solution space is nearly infinite, starting with constraints narrows the space to actually viable options.

SAP consultants develop this thinking because business processes are fundamentally about managing constraints: regulatory constraints, financial constraints, capacity constraints, policy constraints, control constraints. The technically optimal solution often violates multiple constraints, making it practically useless. The consultant's mind has reorganized to see constraints first because that's what determines feasibility.

3. Stakeholder Multiplicity as Default Assumption

Software engineers often design for users, a defined group with presumed shared interests. SAP consultants automatically think in terms of stakeholder ecosystems where interests diverge and sometimes conflict.

When designing a procurement process, the consultant's mind automatically considers: Procurement wants to minimize cost and consolidate suppliers. Operations wants multiple suppliers for reliability and fast delivery. Finance wants simplified vendor management and clear payment terms. Legal wants favorable contract terms and reduced liability. Compliance wants documented controls and audit trails. Each supplier wants to maximize their own advantage.

The consultant literally can't think about a business process without their mind immediately populating it with stakeholders whose interests must be balanced. Research on expert cognition by psychologists Paul Feltovich and Michael Prietula shows that experts develop "compiled" knowledge where conscious reasoning becomes automatic perception. The consultant doesn't think "I should consider different stakeholders," they automatically see stakeholders the way you automatically see objects when you look at a room.

The Integration Imperative: Thinking in Systems Rather Than Components

Perhaps the most profound cognitive shift that business process exposure creates is what systems theorist Donella Meadows called "systems thinking", the ability to see not just components but the relationships and feedback loops between them.

A manufacturing company had an inventory accuracy problem. Physical inventory counts never matched system records. They'd tried improving their counting processes, enhancing their warehouse management system, and implementing RFID tracking, but nothing worked.

A technical consultant would analyze the inventory system: Are we tracking movements correctly? Is the database accurate? Are the transactions processing properly? All technical analysis showed the system was working correctly.

An experienced SAP consultant asked different questions: "Walk me through what happens when you receive material but quality inspection fails. What happens to production scrap that's recorded after the fact? How do you handle customer returns that arrive damaged?"

The issue wasn't the inventory system—it was that multiple other business processes (quality management, production reporting, returns processing) affected inventory without clear handoff points. Each process was designed in isolation, and their interactions created inventory discrepancies that appeared inexplicable when looking at any single process.

This systems thinking doesn't come naturally—it's developed through repeated exposure to business processes where everything affects everything else. Research by system dynamics pioneer Jay Forrester revealed that even intelligent people struggle with systems thinking because our minds evolved for linear causation, not complex feedback loops. We naturally think "A causes B" rather than "A influences B which influences C which feeds back to influence A."

The Exception-Handling Mind: Developing Robust Mental Models

One of the most distinctive cognitive patterns SAP consultants develop is what I call "exception-handling thinking"—the automatic tendency to think about edge cases, unusual situations, and what happens when things don't go as planned.

The 95/5 Problem

Software engineers often optimize for the common case: design for the 95% scenario that happens most frequently. SAP consultants develop cognitive habits that focus equally on the 5% exception cases because those exceptions often determine whether a process actually works in practice.

"What happens if the vendor sends partial delivery? What if they ship the wrong material? What if the invoice arrives before the goods? What if the goods are damaged? What if the approval is on vacation? What if we need to reverse a completed order? What if the customer returns items six months later?"

Business processes fail not because the common case doesn't work, but because exception cases aren't handled. The consultant's mind has been trained through painful experience to automatically generate exception scenarios.

Cognitive psychologist Gary Klein's research on "pre-mortem" thinking—imagining future failure to prevent it—shows this is a learned skill that distinguishes expert decision-makers. SAP consultants practice pre-mortem thinking constantly, developing it as an automatic cognitive habit.

Designing for Actual Behavior vs. Desired Behavior

Perhaps the most sophisticated aspect of exception-handling thinking is the cognitive distinction between how processes should work (desired behavior) and how they actually work (actual behavior).

A client wanted to implement a system requiring three-level approval for all purchase requisitions over $5,000. The process looked elegant on paper. An experienced consultant immediately asked: "What's the average approval time per level? Who approves when someone's on vacation? What happens if an urgent need arises Friday afternoon? What's the current workaround people use?"

The answers revealed that the organization couldn't function with this approval process—urgent needs would be blocked, users would find workarounds, the system would be circumvented. The technically correct process would fail because it didn't account for actual organizational behavior.

This cognitive distinction—between ideal and actual—becomes automatic for SAP consultants. They literally cannot look at a process design without their mind automatically simulating how actual humans in actual organizations will actually behave, including the workarounds they'll create, the shortcuts they'll take, and the ways they'll subvert the intended design.

Research by organizational theorist James March on "logic of appropriateness" reveals that organizational members follow processes not just based on rational calculation but on identity, norms, and situational pressures. SAP consultants develop intuitive understanding of these logics through repeated exposure to the gap between documented processes and actual practice.

Developing Process Thinking: Can It Be Accelerated?

If business process exposure creates genuine cognitive transformation, can that transformation be accelerated through deliberate practice?

Some SAP consulting firms have experimented with intensive process immersion, having new consultants spend their first six months doing nothing but studying business processes across multiple industries and functional areas before doing any implementation work.

The results are mixed. Process knowledge accelerates, but the cognitive transformation seems to require not just learning processes but experiencing the consequences of process decisions. The feedback loop—designing a process, seeing it succeed or fail, understanding why, seems essential for developing robust process thinking.

This aligns with research on expertise acquisition: knowledge can be transmitted quickly, but cognitive reorganization requires extended practice with meaningful feedback. You can teach someone about business processes in weeks, but developing the automatic perception of process dynamics requires years of experiencing those dynamics.

Interestingly, consultants who work across multiple industries seem to develop more robust and transferable process thinking than those who specialize in single industries.

The consultant who's implemented processes in manufacturing, retail, healthcare, and professional services develops cognitive patterns that capture universal process dynamics rather than industry-specific patterns. Their thinking becomes more abstract and therefore more transferable.

This aligns with research on analogical reasoning: expertise becomes more powerful when it's abstracted from specific contexts. The ability to see underlying patterns across different surface manifestations represents a higher form of cognitive organization.

The Ultimate Question: Is Process Thinking Superior?

We've established that SAP consultants develop distinct cognitive patterns through business process exposure. But does this make them "better" thinkers, or just different?

The evidence suggests the answer depends entirely on the domain. For understanding how organizations actually operate, designing processes that account for human behavior, navigating complex stakeholder dynamics, and implementing systems that work in practice—process thinking is demonstrably superior.

For pure algorithmic problem-solving, abstract reasoning, creative innovation, or theoretical analysis—process thinking may be a liability. The consultant's automatic tendency to see constraints, stakeholders, and exceptions can inhibit the free exploration of possibility spaces that pure innovation sometimes requires.

Perhaps the ultimate advantage SAP consultants can develop is meta-cognitive awareness—recognizing their own cognitive patterns and knowing when to apply them versus when to deliberately think differently.

The consultant who recognizes "I'm automatically seeing this through a process lens, but maybe I should consciously try a different perspective" has developed a sophisticated form of cognitive flexibility that transcends any single thinking mode.

Research on cognitive flexibility by psychologist Ellen Langer shows this awareness—being able to see that you're seeing in a particular way and choosing to see differently—represents advanced cognitive development that serves across all domains.

The question isn't whether SAP consultants think differently because of business process exposure. The question is: now that we recognize this cognitive transformation occurs, how do we deliberately cultivate it, accelerate its development, and leverage it more effectively?

Because in a world where technical knowledge becomes outdated quickly and business models evolve constantly, the ability to understand how complex human systems actually operate—to think in terms of processes, constraints, stakeholders, feedback loops, and exceptions—may be one of the most durable and valuable cognitive capabilities anyone can develop.

Have you noticed your thinking patterns changing through exposure to business processes? Do you find yourself seeing the world differently from colleagues of different backgrounds? I'm curious about your experience of cognitive transformation.

English

English

Français

Français

Deutsch

Deutsch

Italiano

Italiano

Español

Español

Contribuisci

Contribuisci

Puoi sostenere i tuoi scrittori preferiti

Puoi sostenere i tuoi scrittori preferiti